When is Water not Water? Exploring Climate (in)action Through Philosophy and Creativity

SUMMARY

Climate education often focuses on action despite Children lacking the political agency to implement their learning. Simultaneously, they aren’t offered opportunities to explore the dynamics of climate action and inaction. This project empowered children as future agents of change by supporting them to explore how to instigate behavioural change around water conservation through engagement with humanities researchers, philosophical dialogues and creative work. It innovated new practices in philosophy with children and young people, augmented the self-esteem of the 56 participating learners and changed their attitudes toward and understanding of humanities research. It created an opportunity for 5 researchers to develop skills in communicating their research and brought 25 families to campus to celebrate the participating children’s creativity. The creation of resources for other teachers based on this project puts in on a pathway to larger scale impact.

Research Description

This project focuses on the Philosophy for Children (P4C) pedagogy working between research and practice. This method of thinking philosophically with children and young people supports groups to investigate conceptually rich questions using their experience and understanding as evidence to answer a shared question that matters for how we live together. In this project, the question focused on whether information or inspiration is more effective in changing behaviours in relation to water conservation. The children participating in the project first met with researchers from Classics, Philosophy, Languages and English on campus and used this lived experience as an example when building an answer to the question together.

The project used the Philosophy for Children (P4C) approach, where groups form Communities of Philosophical Inquiry to collaboratively explore conceptually rich questions. Instead of focusing on facts or top-down information, children use their own experiences as evidence, building shared, reasoned responses to real-world challenges.

Research Base:

The central tool of the P4C pedagogy is the transformation of conventional classrooms into Communities of Philosophical Inquiry. This project operationalised the possibility of P4C as a space for enhancing attention. Attention, as theorised by Iris Murdoch and Simone Weil, is a capacity that can enhance our ability to appreciate the realities of others (both human and non-human.) A conference paper presented at UCD in 2022 and later developed into an article Attentiveness, qualities of listening and the listener in the Community of Philosophical Inquiry outlined the synergies between the practice of P4C and philosophical accounts of attention. This project put these ideas into practice.

Previous research into P4C as an effective tool for supporting conversations between teachers and learners about the climate crisis as part of the symposium Evading Oppressive Hope - Speaking with Young People about the Climate Crisis was presented to researchers at the ESAI (Education Studies Association Ireland) conference in 2022. This project built on the theoretical justification of P4C as a pedagogy that supports conceptual agency- the ability to define abstract concepts for oneself when encountered in experience.

This research base was supported by Dr Lucy Elvis’ significant practice experience across a range of contexts, both within and outside educational institutions such as: Electric Picnic music festival, TULCA Festival of Visual Arts, Draoicht Arts Centre Blanchardstown, Galway County Libraries and Galway City Libraries. Additionally experience supporting new facilitators and creating materials for use in school as part of the modules PI2108 and PI2109 Philosophy in Irish School provided a framework for creating materials to support the researchers from other disciplines who joined the project to understand i) the values of democracy and de-centered authority within the project and ii) to encourage them to approach the children with high expectation. This rich practice experience contributed to the impact of this project by creating an experience that was new and engaging.

Practice Experience:

When is Water not Water? developed methods specifically explored in two existing projects. First, a conceptually focused workshop shared with academics and teachers as part of a conference workshop for P4C practitioners at UCD in 2022 entitled The Present and Future of Doing Philosophy with Children and, second, a project discussing climate justice with young people in partnership with Galway City and County Libraries entitled Fierce Close where young people created a podcast in response to the thinking they did together in philosophical dialogue. The When is Water not Water project adapted these methods in response to a challenge faced by first-level teachers working on water conservation through the Green Schools programme with their learners.

Listen to the podcast here:

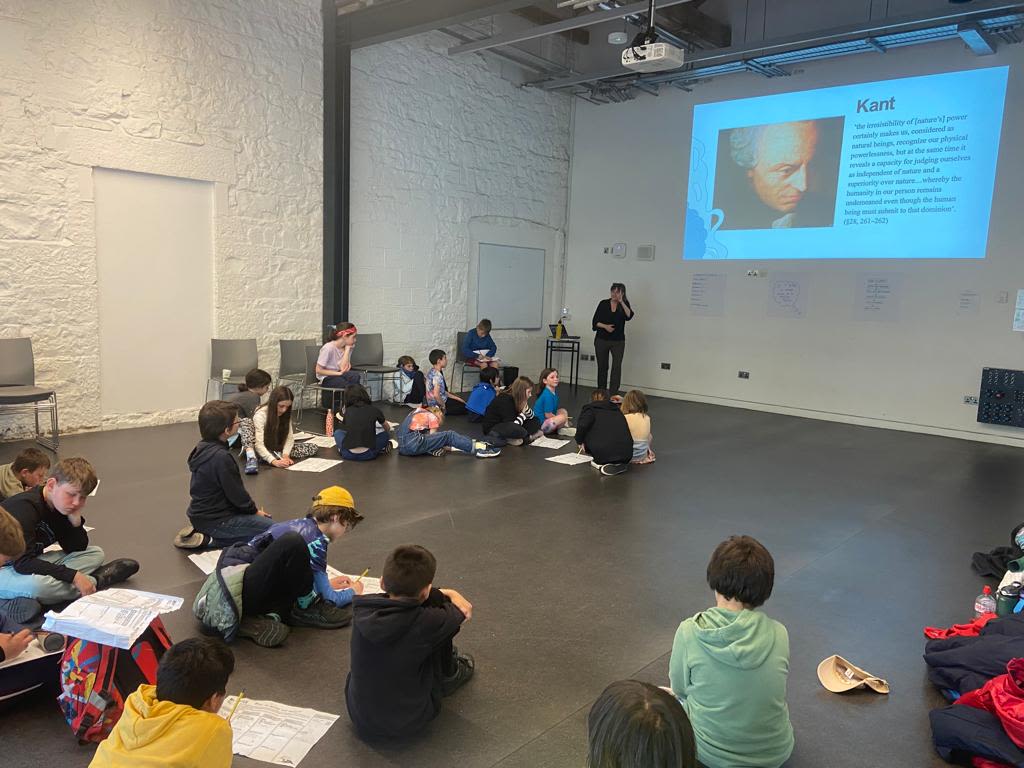

Learning about the day from Dr Lucy Elvis and how to use the note-taking template in O'Donoghue Studio 1

Learning about the day from Dr Lucy Elvis and how to use the note-taking template in O'Donoghue Studio 1

When in the last week did you use water to survive? A snow-ball statues game

When in the last week did you use water to survive? A snow-ball statues game

Dr Sarah Corrigan sharing research on sea monsters in ancient manuscripts

Dr Sarah Corrigan sharing research on sea monsters in ancient manuscripts

Exploring the Sublime with Dr Lucy Elvis, Immanuel Kant and Edmund Burke

Exploring the Sublime with Dr Lucy Elvis, Immanuel Kant and Edmund Burke

When in the last week did you use water to thrive? A snow-ball statues game

When in the last week did you use water to thrive? A snow-ball statues game

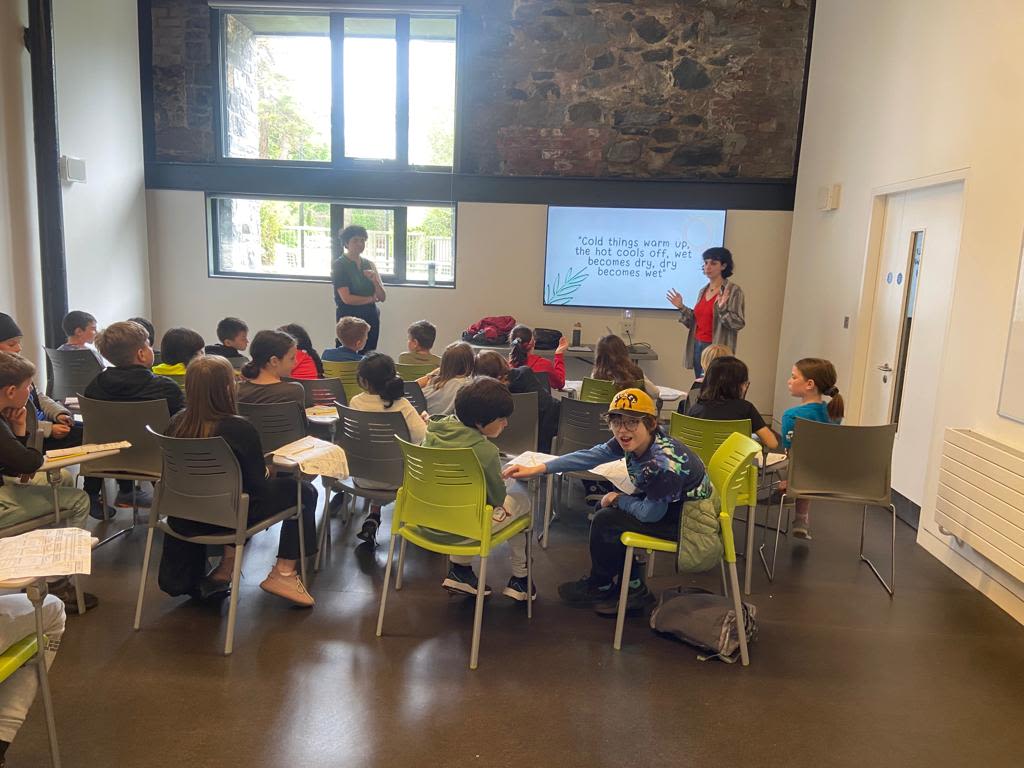

Finding out about water and identity with researchers Michela Dianetti and Julie Agu with help from Heraclitus

Finding out about water and identity with researchers Michela Dianetti and Julie Agu with help from Heraclitus

Project intern Megan Cooke talking about inspiration, information and climate action with a group from 4th class at Knocknacarra Educate Together National School (KETNS)

Project intern Megan Cooke talking about inspiration, information and climate action with a group from 4th class at Knocknacarra Educate Together National School (KETNS)

The project used the Philosophy for Children (P4C) approach, where groups form Communities of Philosophical Inquiry to collaboratively explore conceptually rich questions. Instead of focusing on facts or top-down information, children use their own experiences as evidence, building shared, reasoned responses to real-world challenges.

Details of the Impact

This project responded to a challenge faced by primary school teachers engaging children in learning about water conservation. Conversations with teachers identified that the intangible nature of water and its plentiful nature in Galway was a contributing factor. In response, this project, which focuses on the issues underneath action and inaction in the face of climate emergency, was created. It created a space where rather than being informed about the science of climate change or the actions that ought to be taken, participating children were given an opportunity to discuss water in diverse contexts and define and problematise the ways we try to get others to make different choices.

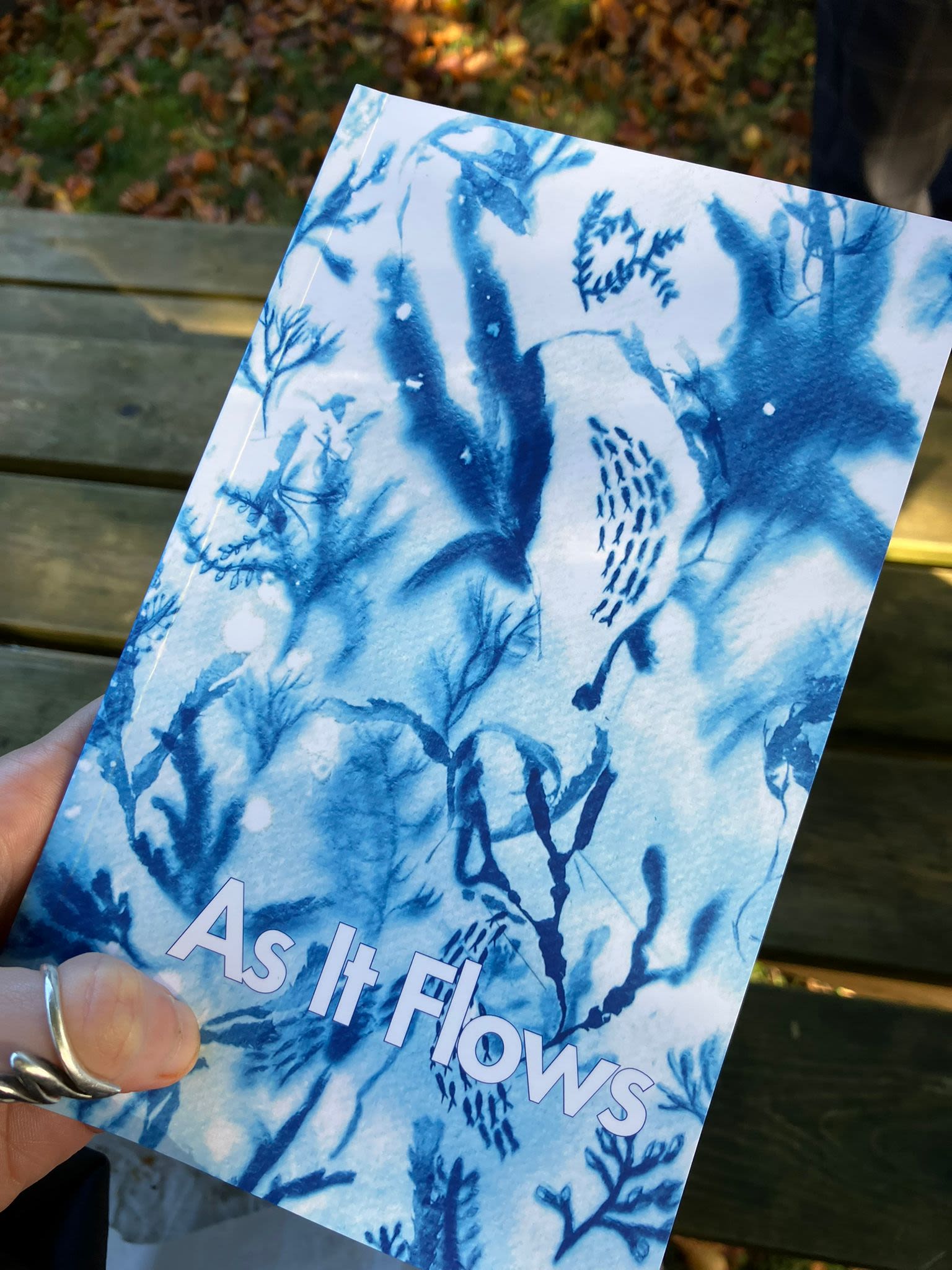

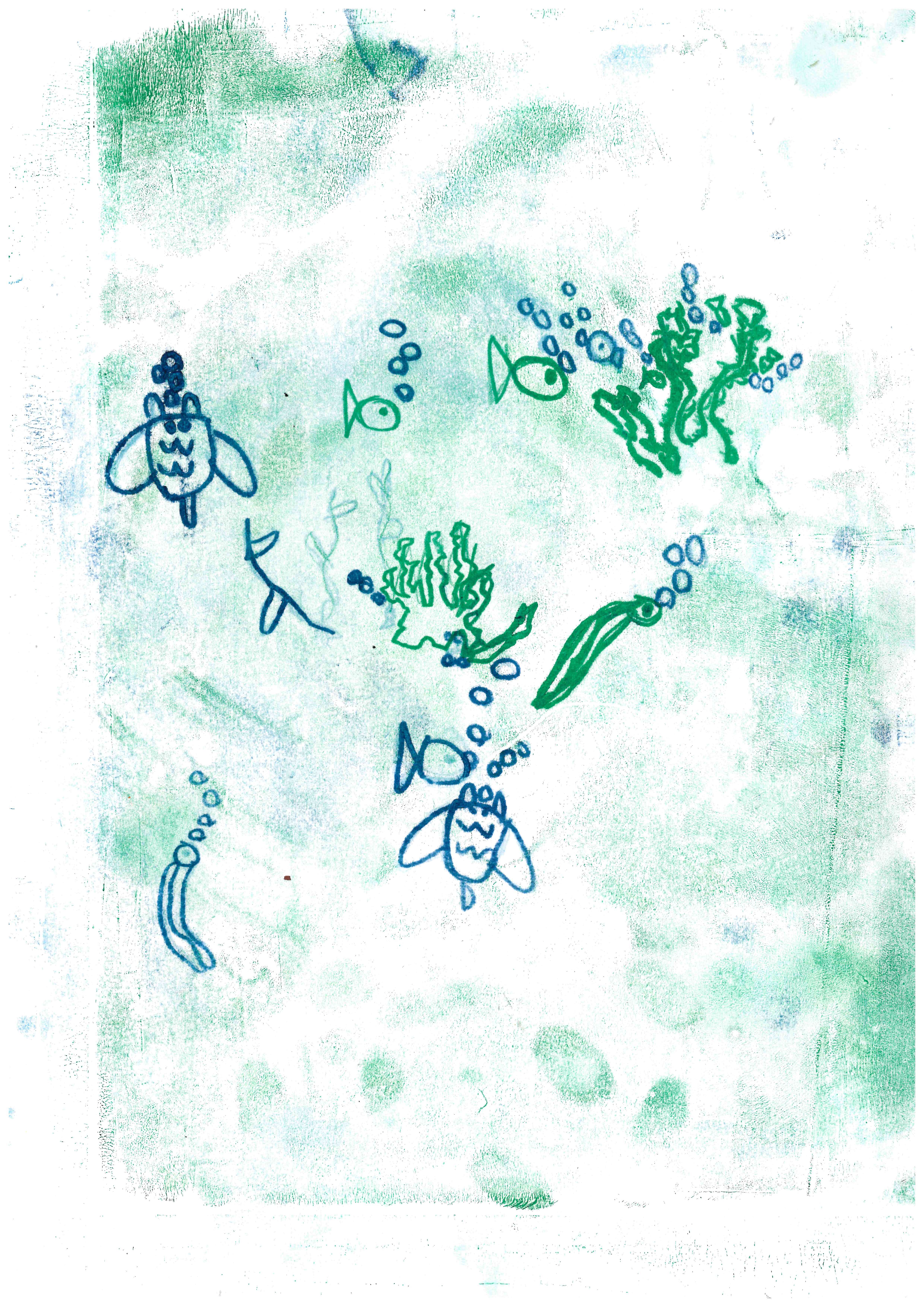

Participating children engaged with researchers through carefully structured, on-campus workshops, used these workshops as examples in facilitated structured dialogue and to created new writing and illustrations based on their thinking which was edited together as a book that launched on campus.

Book created as a part of the project 'When is Water not Water?' by pupils from Knocknacarra Educate together and researchers at University of Galway led by the discipline of Philosophy.

Book created as a part of the project 'When is Water not Water?' by pupils from Knocknacarra Educate together and researchers at University of Galway led by the discipline of Philosophy.

The experience made a lasting impression on participating children and their families, as one parent reflected:

‘This workshop had a fantastic impact on my child (age 10). By opening the doors of the university community and sitting in the workshop sessions she came home overflowing with enthusiasm about the ideas, what we know about water, and the myths surrounding it. She thoroughly enjoyed having been assigned some tasks to build her notes up afterwards. She looks back at that little book from time to time, which has her work in it, and has a very tangible sense of the worth of thinking and how her thoughts have value. I'm immensely grateful she got this unique opportunity.’

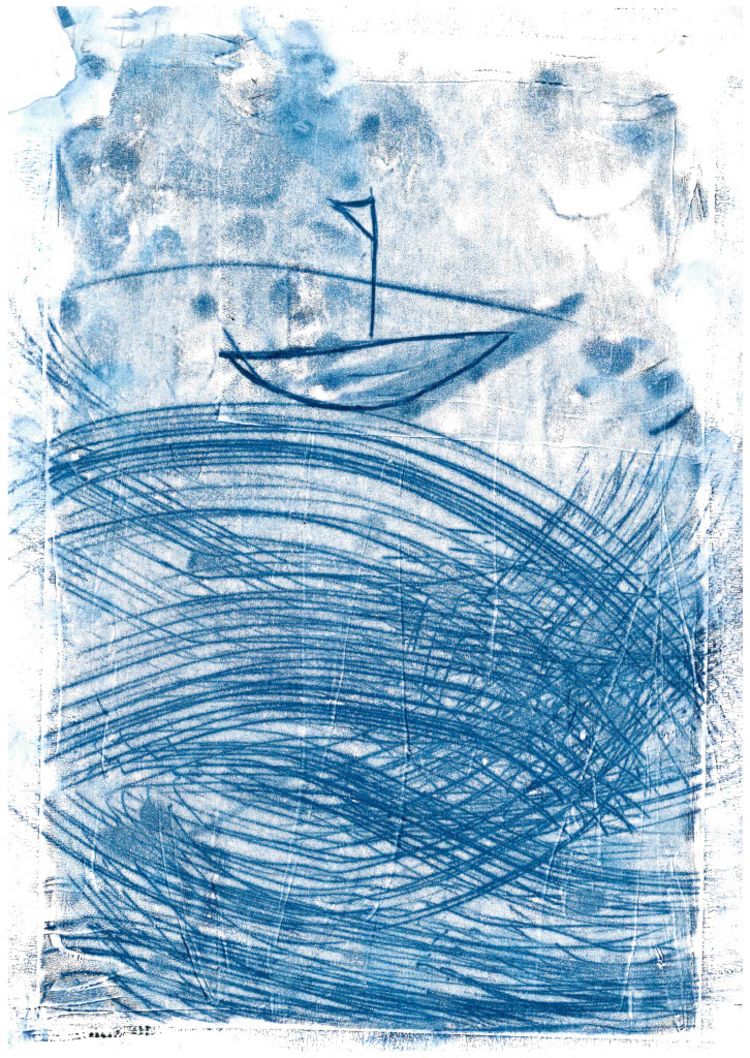

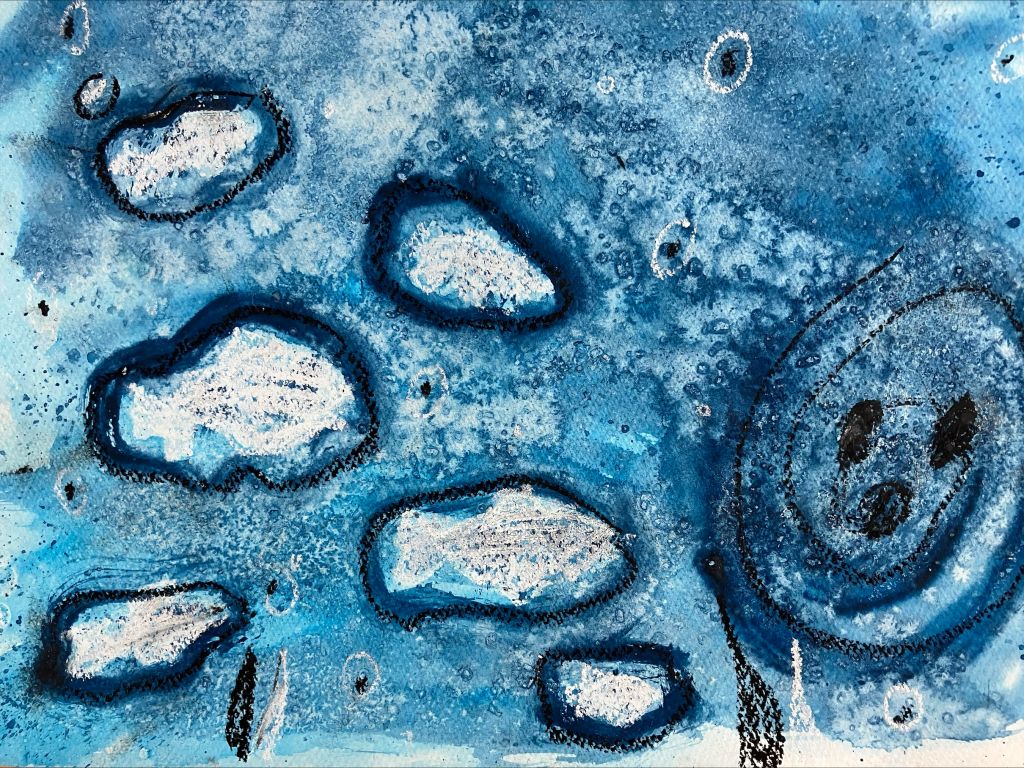

Monoprint Illustration by Aoife 4th Class KETNS

Monoprint Illustration by Aoife 4th Class KETNS

This project was supported through a research development grant from the University of Galway College of Arts Social Sciences and Celtic Studies. The amount received was €5000. Project lead: Dr Lucy Elvis Associate Researcher: Michela Dianetti Undergraduate intern: Meghan Cooke. Campus workshop partners: ECR researchers Dr Sarah Corrigan (Classics) and Dr Eavan O'Dochartaigh (English) and PhD researcher Julie Agu (Languages.) Collaborator: Knocknacarra Educate Together National School, Galway City. Engagement numbers: 2 Teachers, 4 support staff, 59 children, 34 parents, 4 researchers, 1 undergraduate intern.

This was a small project, and its impacts were deep and small-scale. In the next phase of the project impacts will be scaled up through the creation and dissemination of resources based on the project for teachers to use. The project engaged with 58 learners from the 3rd and 4th classes, aged between 8 and 12, at Knocknacarra Educate Together School. This project was designed in response to teachers expressing difficulty in capturing students' interest in water conservation, given how intangible saving water can be in comparison to more direct interventions in the environment (for example, picking litter in your local area or learning about food production by growing your own.)

Project Phases:

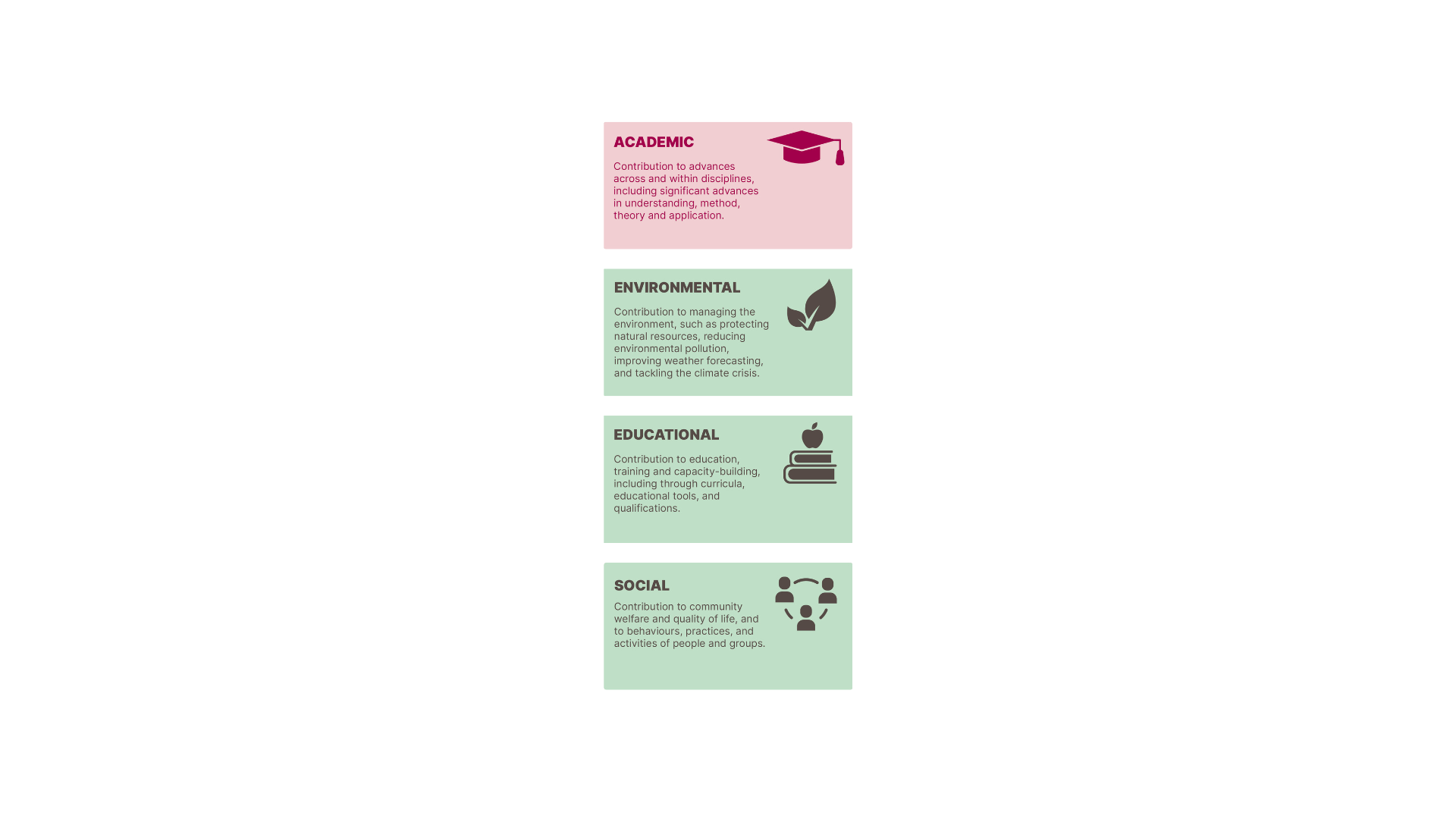

Impacts can be understood as deeper understanding, increased capacities and new possibilities.

Greater Understanding: New understandings were developed by the children, teachers and researchers.

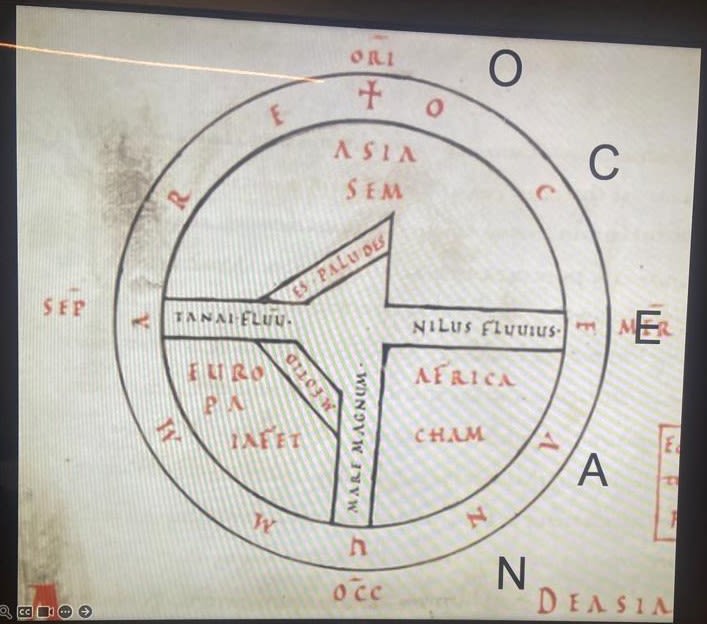

The Children and teachers gained an understanding of who researchers can be and how research interests develop through the workshops on campus in phase one of the project. Children acquired new knowledge about areas of the humanities not taught in the primary or secondary curriculum such as classics and philosophy, and expressed appreciation for these ideas. One good example of this was the fascination the children had for the T-O map and a medieval map that shows water as the edge of the known world. Dr Sarah Corrigan showed this image to the children in her workshop on water in ancient manuscripts.

The T-O Map

The T-O Map

The TO Map by Nevin 3rd Class KETNS

The TO Map by Nevin 3rd Class KETNS

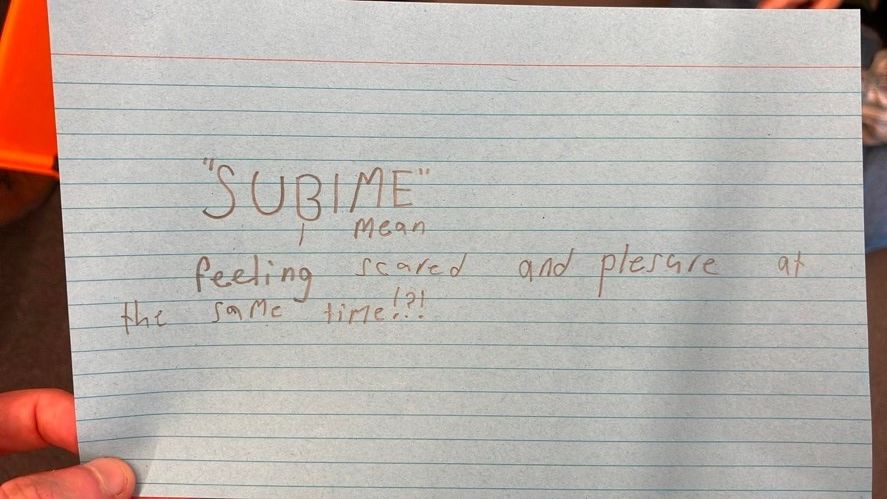

During a workshop on the idea of the sublime, one eight-year old boy was able to define commonplace uses of the world sublime for his peers when the term used (in relation to a goal scored by the footballer, Messi.) Teachers reflected that this discussion, the philosophical dialogues that took place in school and the creative writing the children produced, revealed their learners as capable creatives and thinkers through their philosophical dialogues and creative work.

Figure 1 Student note in response to the question 'Which idea will you keep with you?' the end of the on-campus workshops. Evidence of their grasp of new, unfamiliar ideas.

Figure 1 Student note in response to the question 'Which idea will you keep with you?' the end of the on-campus workshops. Evidence of their grasp of new, unfamiliar ideas.

As testimonials show, the participating researchers understood the relevance and benefit of engaging with children about their research differently. In the case of Dr Eavan O’Dochaitaigh, the teacher in 4th class used the introduction of her academic book Visual Culture and Arctic Voyages (2022) as a ‘read together’ text since their meeting her on campus had captured their curiosity.

Monoprint illustration by Erik 4th Class KETNS

Monoprint illustration by Erik 4th Class KETNS

Increased Capacities: Students increased their capacities to engage in dialogue together. Facilitator notes evaluated by the team after dialogue sessions in schools identified that students defined abstract concepts, presented examples and counter-examples, and referenced the ideas offered by others in their class as they tried to account for the relationships between information and inspiration.

To support the participating students to recognise these capacities in themselves and others, researchers wrote one personal ‘appreciation’ for each participating child recounting a time when their thinking mattered. For example: ‘In our discussion about information and inspiration you talked about how important it is for someone to want to change the way they act- this helped us link our discussion back to looking after water. Thank you for keeping us focused!’ Parents reported that this was powerful in the children understanding themselves as making a contribution that mattered, some of them hanging the appreciation on their wall. In the post-project survey parents commented that ‘[the children] were so proud of their work, and having it published. Really boosted their confidence.’

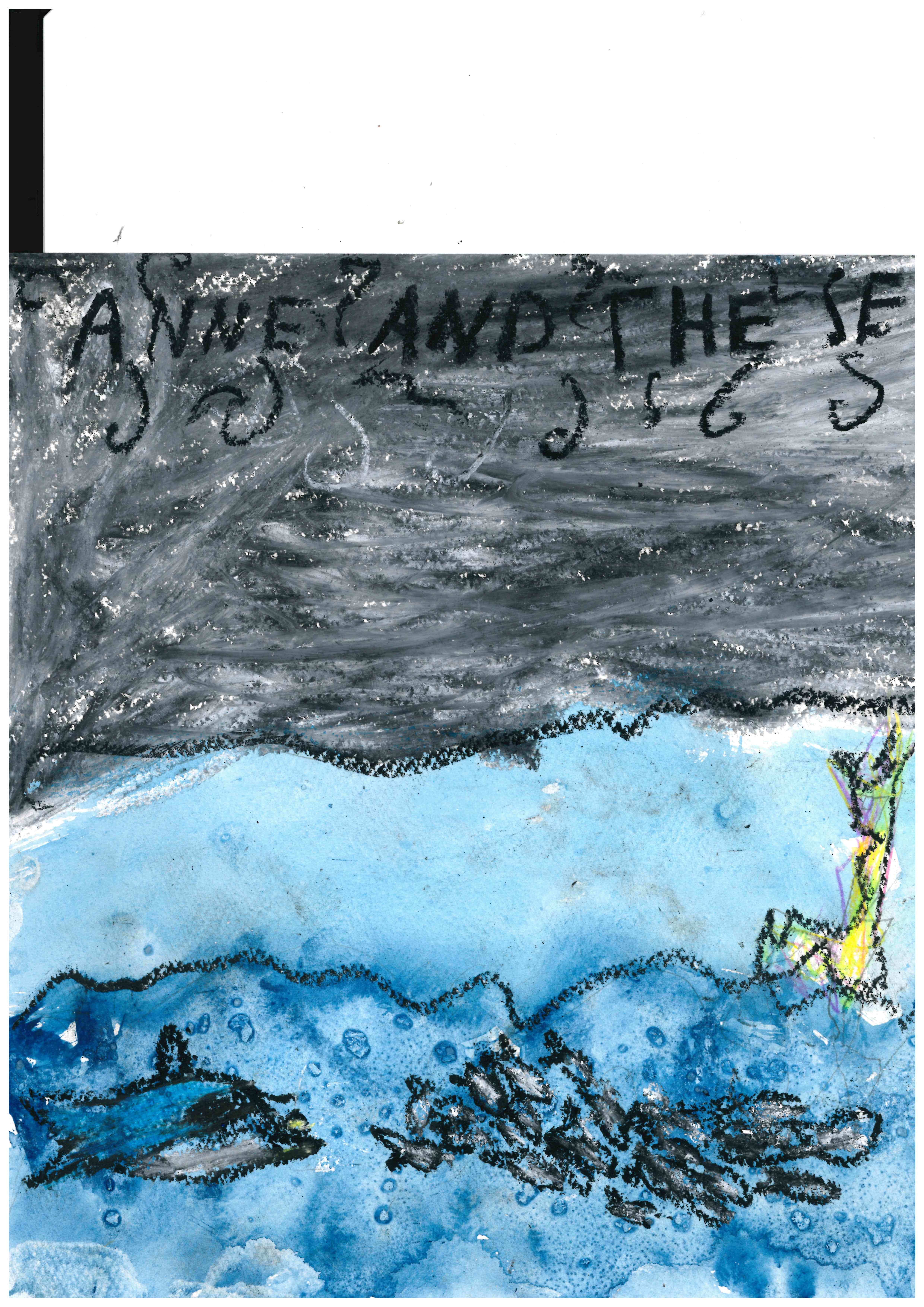

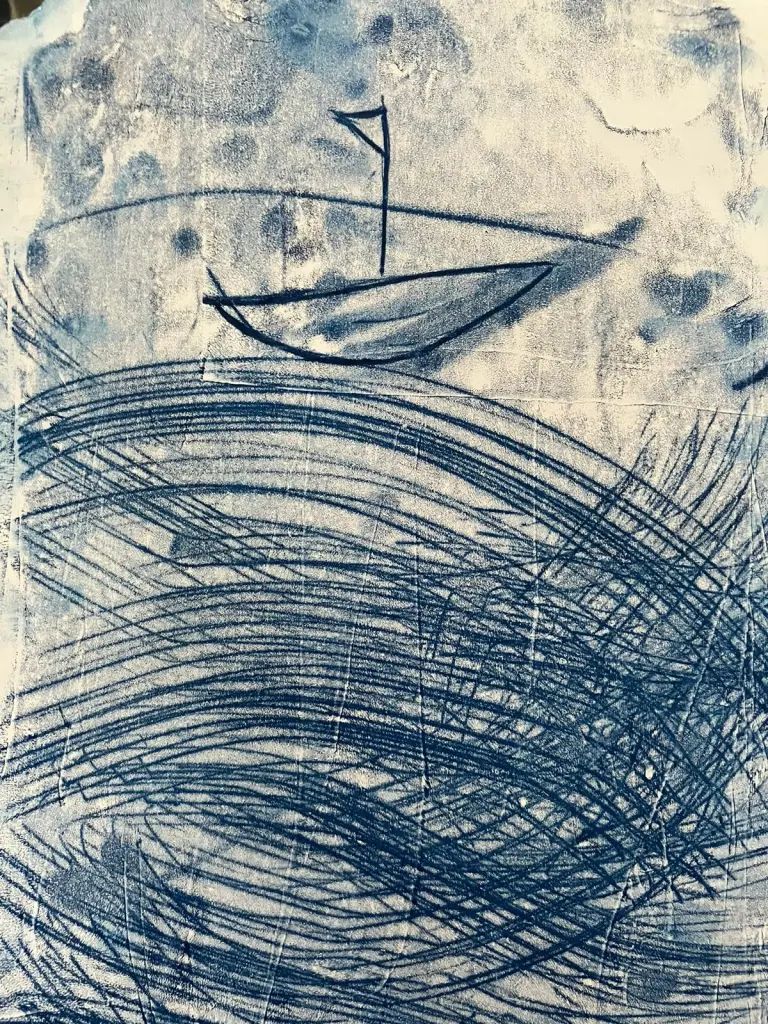

Illustration for Anne and the Sea Storm by Mia A (3rd Class) inspired by the workshop on the Sublime

Illustration for Anne and the Sea Storm by Mia A (3rd Class) inspired by the workshop on the Sublime

Through the artist-facilitated workshops, teachers learned new methods for image making that they intended to incorporate into their art teaching.

Including an undergraduate intern in the project team gave someone at the beginning of their academic journey an understanding of research design delivery an implementation.

New possibilities: The participating teachers understood the value of participating in research and the school has since engaged with a research project in the discipline of Children’s Studies and has reached out for support in having philosophical discussions about friendship among students in 3rd 4th and 5th class. Participating researchers understood themselves and their research in new ways as testimonials show.

84% of parents reported that their children discussed their visit to campus at home, with one commenting that

‘[it] blew my child’s mind that she could talk about and ask knowledgeable researchers about Greek myths and philosophy- her mind was absorbed by the reality that people think about and work on this.’

This project was used as a template for AIRE Attentive Inquiry Reclaiming Environment, which builds on the success of this project to create attention-inspired inquiry activities for inter-generational groups.

Watercolour salt and oil pastel illustration by Nevin, 3rd class KETNS

Research Funding

This research was supported by the College of Arts, Social Sciences and Celtic Studies Research Development Grant

References to the Research

- R1. Information about the pedagogical approach is available on the project website: https://wheniswater.wordpress.com/

- R2. Practices within this project were developed through initiatives and teaching within the Philosophical Dialogue Project

- R3. Theoretical ideas explored through the following publication: Elvis, L. ‘Attentiveness, qualities of listening and the listener in the Community of Philosophical Inquiry’ Childhood and Philosophy http://educa.fcc.org.br/pdf/childphilo/v19/1984-5987-childphilo-19-e76451.pdf

- R4. This project developed work on climate justice initiated through work with the Galway County Libraries service that led to the Fierce Close podcast. Episode available here: https://open.spotify.com/episode/5GT4CMwptnjciTE0imi58v?si=f3cf8439e3be4aca

- R.5 The relationship between the Philosophy for Children Pedagogy and Climate education was explored within the Symposium Evading Oppressive Hope, Talking with young people about the Climate Crisis, shared at the Education Studies Associate of Ireland Annual Conference 2023.

Evidence of Impact

- E1. Evidence of parent reactions to and reflections on the project gathered by an anonymous survey can be found here.

- E2. Excerpt of the book created by the learners in the project: https://issuu.com/wheniswater/docs/online_sample

- E3. Testimonial one: Dara Cannon (parent of a participating child) ‘This workshop had a fantastic impact on my child (age 10). By opening the doors of the university community and sitting in the workshop sessions she came home overflowing with enthusiasm about the ideas, what we know about water, and the myths surrounding it. She thoroughly enjoyed having been assigned some tasks to build her notes up afterwards. She looks back at that little book from time to time, which has her work in it, and has a very tangible sense of the worth of thinking and how her thoughts have value. I'm immensely grateful she got this unique opportunity.’

- E4. Testimonial two: Dr Sarah Corrigan (participating researcher) ‘This project was intriguing in the way that brought apparently disparate elements together in order to achieve its ultimate aim. From the outset, I was aware that this aim was to engage these cohorts of primary school children in a philosophical enquiry about the impact of information and inspiration in order to open up ways of thinking about water resources and their management. In my own contribution, one of several researchers at the University of Galway, I shared medieval perceptions of the ocean, its creatures (real and imagined), and the nature of the ocean as a component of medieval cosmology. The interactions that I had with the students during the workshop impressed upon me the power of presenting even young students with historical texts and imagery in the context of their academic significance, not simply as simplified or mythologised narratives. The students responded with shrewd questions and unexpected insights about the nature of these materials and the people and societies who produced them. The contributions that the participants produced in response to the materials I presented showed a depth and breadth of responses far beyond those I had imagined. They translated not only the content of the materials into their writing and illustration but also important concepts in the understanding and critique of those materials. Fundamentally, participating in this workshop exploded my understanding of how to present early medieval culture to young learners. This experience is currently feeding into my teaching of a third-year undergraduate subject here at the University of Melbourne. This subject, Underworld and Afterlife, is populated with both Classics and Ancient World majors, but also breadth students from across the University's disciplines. What is often appealing to a wide audience such as this are the attractive mythological elements or the 'exotic' seeming practices and material culture; however, as was the case in the When Is Water Not Water, it is clear that that the foundational value of this subject material is the ways that it speaks to, informs, and encourages creative thinking on modern philosophical and cultural issues.’

- E5. Testimonial three: Researcher Michela Dianetti. "When my friend Julie and I were preparing our workshop on ‘When Water is a Puzzle’, we were excited by the idea that, for children without parents or relatives in academia, this might be their first encounter with a university. We felt a sudden responsibility to introduce research in the humanities as something that, even in our modern technological world, can still shift our attention to things that matter to us as human beings, such as caring for the environment. Playing with the word ‘water’ and its various symbolic, cultural, and metaphorical meanings got us thinking about how paying attention to the words we use every day and their meanings, especially in our linguistically dry times, helps shape what we see and how we act in the world. " After philosophically inquiring into the problem of inaction in relation to climate change in the second phase of the project, I was particularly moved by our collective effort to populate water through our imaginations with exotic monsters and familiar creatures, viewing water as an ever-changing element—a metaphor for change, as in Heraclitus’ image of the river, which we explored in the ‘When Water is a Puzzle’ workshop. This experience provided me with a tangible sense, which often feels abstract in my theoretical research, that philosophy and art, -- the collective exploration of concepts and the use of imagination – have a true and necessary potential to inspire us to change our way of looking at our world and what matters. On a personal level, explaining my research field, the philosophy of literature, to the young participants helped me understand it a bit more. Breaking down a complex argument to its fundamentals, without oversimplifying it, made it suddenly clearer to me as well. As a PhD researcher always doubting her project (an inherent part of the PhD experience!), this clarity made me very happy. This project was a beautiful example of what I think philosophy, and the humanities in general, should aim for in our modern times: bridging the gap that relegates them to an elitist group of specialists and opening wide the doors of the university, engaging the community starting with the most unheard voices—the children.’

- E6. AIRE Attentive Inquiry Reclaiming Environment Project Website. This project was developed out of the models created in the When is Water not Water initiative: https://aireinquiryandenvironment.wordpress.com/